Drinking Water Treatment Process | How to Process Drinking Water | Types of Drinking Water Procedure

Life requires water, and access to clean drinking water is essential for health. Every day, 400 people worldwide pass away from infections in contaminated drinking water. The bulk of the water on Earth needs to be treated before it can be utilised, even though some of it is pure enough to drink. The process of treating water involves removing contaminants from it, including bacteria, viruses, chemicals, industrial waste, solids (such as dirt and dust particles), and naturally occurring metals from the soil. Unwanted tastes or odours are also eliminated during water treatment. When it is collected, at a sizable governmental facility for cities and towns, or at the point of use, like a faucet, it can be treated. Water needs to be treated once more after usage to prevent toxins from being released back into the environment. Before being sent to the lakes and streams, wastewater also undergoes a number of processes to eliminate any impurities.

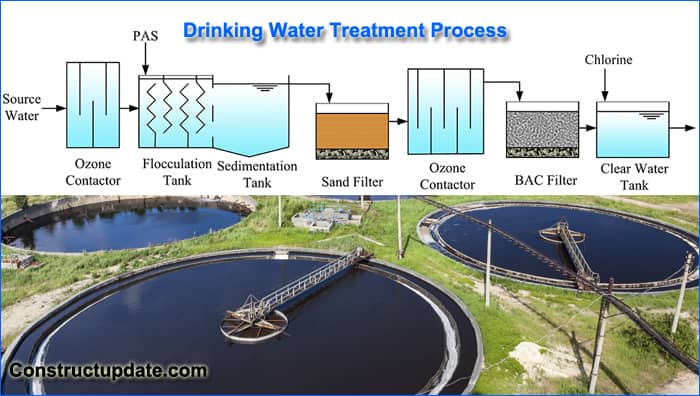

Water Treatment Process

Water is treated before it reaches a building, place of business, or school to make sure it is odourless and safe to drink. Water treatment facilities use pumps to transport water from the ground or a reservoir, like a lake. Here, toxins and pathogens are removed from the water before it reaches the user using contaminant removal agents, which can be categorised as chemical, physical, and biological procedures.

1. Collection

Before it can be treated, water must first be drawn from reservoirs, rivers, and lakes. The water is often transported from the source to the treatment facility using a complex network of pumps and pipelines, notwithstanding the possibility of using natural ways (such as rivers).

2. Screening

The first step in the treatment process is screening the water, which removes larger suspended objects including trash, plants, trees, animals, and other debris. They are removed and captured using a sizable metal screen, as the name implies.

There are coarse and fine screens.

Coarse screens are made of corrosion-resistant steel bars that are spaced 5 to 15 cm apart and are used to keep coarse waste (such as logs and fish) out of the treatment plant. The screens are set up at a 60-degree slant to make the mechanical raking of the gathered material easier.

Following the coarse screens, the fine screens filter out anything that can obstruct the plant’s pipes. They are made up of 5 to 20 mm-apart steel bars. The micro strainer is a kind of fine screen that has a mesh size that ranges from 15 micrometres to 64 micrometres, or from 15 to 64 millionths of a metre. It is constructed from a mesh drum of stainless steel that rotates. You can catch suspended materials like plankton and algae, which are tiny organisms that float in the water with the stream. The trapped sediments are transported for disposal after being released from the cloth using high-pressure water jets and clean water.

3. Chemical addition

Chemicals are being used to encourage minute suspended matter particles to coalesce and form “floc.” Coagulants, which are the chemicals utilised to accomplish this goal, come in a wide variety of items.

4. Coagulation

To allow the flocs to form, the water must be agitated with the coagulant at various speeds for a while after it has been applied (this part of the process is known as flocculation).

Now that the charges of the microscopic particles are equalised, they unite to create “flocs,” which are soft, fluffy particles. Ferric chloride and aluminium sulphate are two coagulants that are frequently employed in the treatment of water.

The following action is flocculation. Here, as the water is gently moved by paddles in a flocculation basin, the flocs interact with one another to form larger flocs.

Smaller compartments with slower mixing rates usually form as the water passes through the flocculation basin. Increasingly huge flocs can grow in this divided chamber without being dispersed by the mixing blades.

5. Sedimentation and clarification

Once the flocs have formed, the water is next directed across a sedimentation basin. Here, the floc particles may collect before being recovered and thrown in a pond. They may also settle to the bottom of the basin.

6. Filtration

The water must now be filtered using a variety of media, such as sand, gravel, or granular activated carbon, to remove the tiny undesirable particles that are still present after the bigger particles have been removed.

When there are a lot of solids caught in the filters, they are back-washed. If there is a sewer system, the dirty water, known as backwash, is poured into it when contaminants are caught in the filter and clean water and air are forced back up the filter to release them. As an alternative, it might be returned to the parent river after settling in a sedimentation tank to remove sediments.

7. Disinfection

The majority of the remaining contaminants have now been eliminated from the water, but bacteria, viruses, and other microbes may still be present. It must be treated with just the right amount of chlorine to destroy these contaminants without impairing flavour or odour.

8. Storage

Even if the water has been basically prepared for public consumption, it still needs to be stored until it is needed. Above-ground or below-ground storage tanks are the most common type of container. Both drinking water and water that can be stored for situations like fires must be available.

9. Distribution

Water is ultimately delivered to homes and businesses across the country using a complex network of pumps, tanks, pipelines, hydrants, valves, and metres.